Uzbek Dance and Culture Society

|

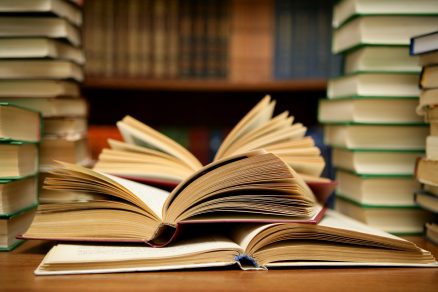

Embassy of Uzbekistan hosts book presentation by Laurel Victoria Gray

on May 22, 2024 to standing-room-only audience. Uzbek Dance in Laramie, Wyoming

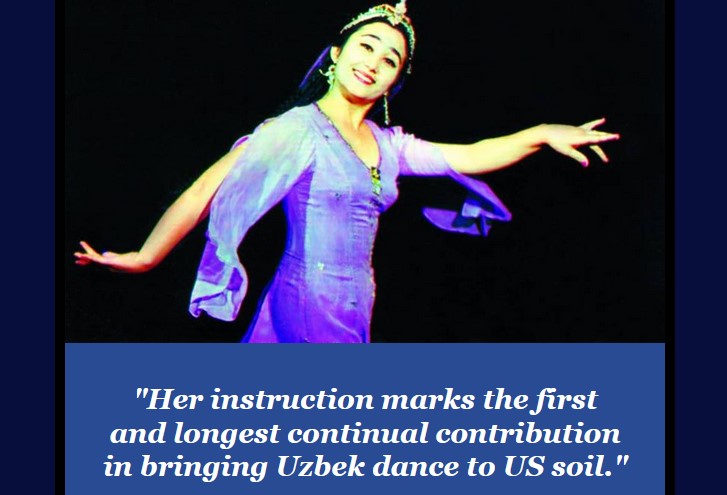

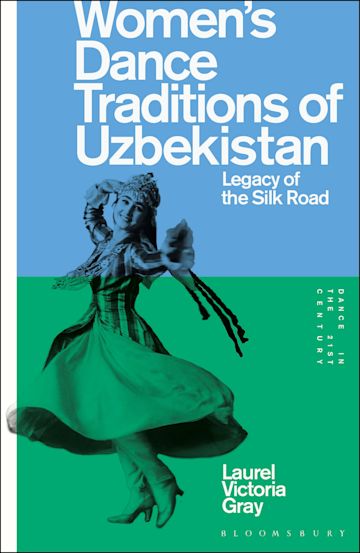

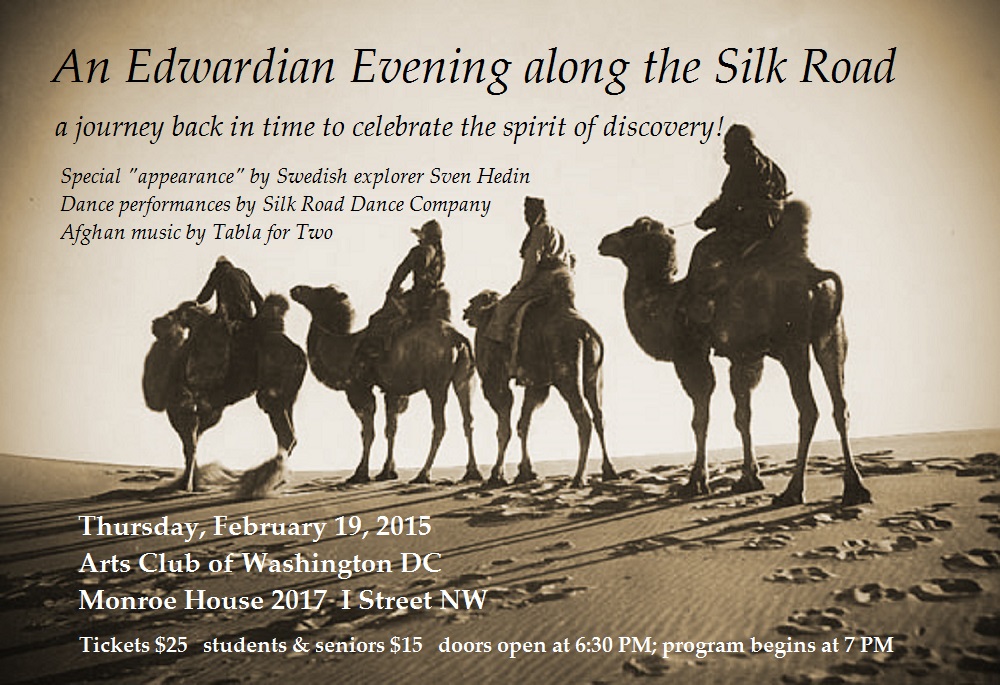

Skylar Lewis, Guest Writer University of Wyoming Laramie, Wyoming Tuesday, April 23, 2024 As part of the University of Wyoming Central Asian Student Association (CASA) Central Asian Awareness Day and Navruz celebrations, the renowned choreographer, dance scholar and founder of the award-winning Silk Road Dance Company, Dr. Laurel Victoria Gray, also referred to as “the pioneer of Uzbek dance in America,” was invited to UW's campus for two days of presentations and performances from the Silk Road Dance Ensemble. Michael R. Brown, the UW Emeritus Communications and Journalism professor, who has been working with students and professionals from Kazakhstan since 2012, spoke on the significance of Dr. Gray's work in Central Asia. “Uzbekistan was at the crossroads of the Silk Road with influence from Turks, Persians, Arabs, Chinese, Uyghurs and Russians, among others. While many Americans may not be familiar with this part of the world, to have an opportunity to work in this part of the world and share it as both very interesting and very important.” “Dr. Gray's work has received international recognition by the most important academic and cultural organizations who honor dance... she has been named Honorary Professor at the Uzbekistan State Institution of Arts and Culture, invited to participate in Uzbekistan's State Academic Bolshoi Theater, participated in UNESCO's Sharq Taronalari Festival in Samarkand, honored by the Ministry of Culture in Uzbekistan,” and received a Distinguished Service Award from the Embassy of Uzbekistan,” Brown said. “To be honored by the culture you represent is the highest honor, and a true indication of honesty, accuracy, and high achievement in her work to understand Uzbek dance,” he said. On Thursday, Dr. Gray took to the Coe Library to not only give a detailed lecture about the long, and at times suppressed, history of dance in Uzbekistan, but also to announce the official publishing of her book, Women's Dance Traditions of Uzbekistan: Legacy of the Silk Road, of which free copies and signings were offered to the attendees present at the lecture. Dr. Gray's presentation illustrated a brief timeline of how this cultural aspect of the Uzbek people, particularly Uzbek women, came to manifest itself, the challenges that women faced and overcame to perform this art in public. While the lecture gave a more encompassing view of the region's history, Dr. Gray's book offers a much more comprehensive overview and further insight into the social into the political, social and cultural aspects of the Silk Road region that calls itself home to Uzbek dance. Friday featured a set of related events from Dr. Gray, her Silk Road Dance Ensemble and well-known dancer and musician, Zamira Salim, as part of CASA's 12th annual Navruz celebration, an event or festival which normally falls on or around March 21 and is widely celebrated in many Central Asian countries like Uzbekistan as the beginning of spring, or the vernal equinox commences. The event was hosted in the Wyoming Union ballroom, and had an impressive turnout, with nearly every seat being taken up by its attendees. Excited to see a live performance of Uzbek dance, and share a free meal in turn. After some short introductions from CASA’s student president, and Brown, as well as an opening performance from Salim, Dr. Gray introduced herself, her dancers, as well as some of the historical context for their performances, the first of which Dr. Gray introduced as “Kara Jorga,” or “Black Stallion.” “Greetings dear guests, dear friends,” Gray said. “We're going to take you on a whirlwind tour of Central Asia through dance and the very first place we are going into is Kurdistan [actually Kyrgyzstan], which may seem far away with nothing in common with Wyoming, but you would be wrong because I've seen all the equestrian statues in this town. So we brought you some horses, well actually, horseback riders.” Following the performances of Salim, Dr. Gray’s Silk Road dancers who performed “Black Stallion” and a solo traditional Uzbek dance for attendees, was a short intermission as organizers of the event began to call up tables to serve a traditional Central Asian style dinner, which was provided to the event by one of its sponsors, Thai Spice. As attendees enjoyed the food and company of others, they were offered consistent entertainment through the rest of the Navruz celebration as the Silk Road Dance Ensemble continued to perform several cultural dances for the crowd until the event’s end. * SPECIAL THANKS TO DR. DILNOZA KHASILOVA for coordinating this multi-faceted cultural event. In Loving Memory of Our Ustoz

|

|

|

|

Government of Uzbekistan Awards

Laurel Victoria Gray

the 'Xalqlar Dosligi" Medal

From Uzbek Ambassador Javlon Vakhabov:

"A wonderful evening The Embassy of the Republic of Uzbekistan in the U.S. and Canada hosted yesterday [October 28, 2021] launching the 18th Central Asian Dance Camp. It was my great honor to present the award “Friendship Among The Peoples” to Laurel Victoria Gray (Silk Road Dance Company) for her invaluable contribution to enhancing people-to-people ties and promoting #Uzbekistan culture in the U.S.

Laurel Khanum has not only dedicated her life mastering Uzbek dance in the U.S. and far beyond, but also remains most humble, professional, and passionate about what she is doing. And this lady is an internationally recognized scholar, choreographer, performer, costume designer, pioneer of Uzbek dance in America. I am inspired by her noble personality that always searches for new discoveries.

Laurel Khanum has mastered dances from Silk Road cultures and beyond. She combines her degrees in history with decades of field research and teaches dance at The George Washington University. Dr. Gray founded the award-winning Silk Road Dance Company (SRDC) in 1995, bringing the lovers of our culture together at the Central Asian Dance Camp annually, showing the beauty during many events across the U.S. and far beyond.

Dr. Laurel Victoria Gray, in one word, is our treasure in the U.S. Thank you for everything you have been doing over the years. I hope to continue our long-lasting friendship."

"A wonderful evening The Embassy of the Republic of Uzbekistan in the U.S. and Canada hosted yesterday [October 28, 2021] launching the 18th Central Asian Dance Camp. It was my great honor to present the award “Friendship Among The Peoples” to Laurel Victoria Gray (Silk Road Dance Company) for her invaluable contribution to enhancing people-to-people ties and promoting #Uzbekistan culture in the U.S.

Laurel Khanum has not only dedicated her life mastering Uzbek dance in the U.S. and far beyond, but also remains most humble, professional, and passionate about what she is doing. And this lady is an internationally recognized scholar, choreographer, performer, costume designer, pioneer of Uzbek dance in America. I am inspired by her noble personality that always searches for new discoveries.

Laurel Khanum has mastered dances from Silk Road cultures and beyond. She combines her degrees in history with decades of field research and teaches dance at The George Washington University. Dr. Gray founded the award-winning Silk Road Dance Company (SRDC) in 1995, bringing the lovers of our culture together at the Central Asian Dance Camp annually, showing the beauty during many events across the U.S. and far beyond.

Dr. Laurel Victoria Gray, in one word, is our treasure in the U.S. Thank you for everything you have been doing over the years. I hope to continue our long-lasting friendship."

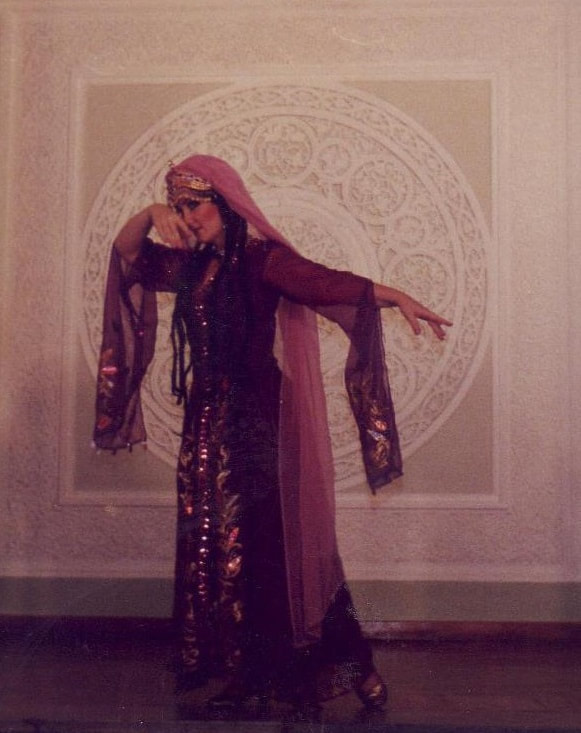

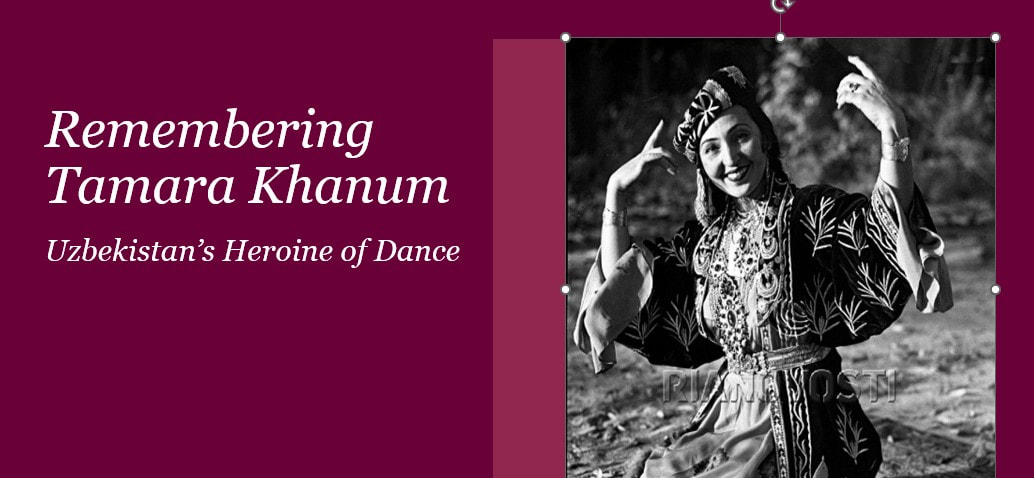

Remembering Tamara Khanum

Uzbekistan's Heroine of Dance

by Laurel Victoria Gray

PREFACE:

In 1984, as a member of an official delegation visiting Seattle’s sister-city, Tashkent, I received a rare invitation to the home of People’s Artist of the USSR, Tamara Khanum, the first woman in Uzbekistan to dance in public. The excerpts below come from my article, "Tamara Khanum: Uzbekistan's Heroine of Dance," which originally appeared in a 1985 issue of Arabesque Magazine and is reprinted here with their permission.

All great dancers sacrifice for their art, but very few risk their lives in this endeavor. Tamara Artemyevna Petrosian[1] placed her life in jeopardy merely by dancing, for the arena she chose was a public one in a land where women courted death for daring to appear unveiled. In her dedication to her art, Tamara became a revolutionary heroine.

Born in the Ferghana region in 1906, Tamara Khanum absorbed the culture and traditions of the Uzbek people although her lineage was Armenian. As a child in pre-revolutionary Turkestan, she grew up in a society where women led circumscribed lives, venturing into public only when concealed in the paranjah.[2] “Women were never allowed to speak with strangers, much less sing or dance in front of them.” [3] Women confined their dancing to the ich-kari, the women’s quarters, and danced for each other.

During the 1920s, when the Bolsheviks consolidated their power, social reforms - including the emancipation of women - accompanied their political and economic changes. In 1927, women gathered in Samarkand’s Registan Square to burn their veils. Many earned death for their boldness.

Tamara Khanum opened a new era for Uzbek arts. Her bravery became a political act when she brought ancient dances out into the brilliant light of the 20th century; public appearances were fraught with genuine danger. She became the target of the Basmachi: traditionalist, anti-communist bands of partisans which challenged Soviet authority. “The Basmachi tried many times to kill me,” recalled Tamara Khanum, “but I escaped. The people helped me; they hid me.” Not all were so lucky. She pointed to an old photograph of a delicate young woman.[4] “She was my student,” Tamara Khanum explained, “but she was killed.” Her grief was still fresh.

The times required that an artist also be a fighter.[5] Those early years passed without glamour or ease. “I danced anywhere,” Tamara Khanum reminisced, “on rooftops, in the streets, in the villages. I remember walking with the baby at my breast, another child at my side, holding my hand, and on my back, a bundle filled with my costumes. Like this I walked to the villages and danced, while in the audience sat women still wearing the paranjah.”

She took her art to Paris where, in 1924, she performed at the World Exhibition of Decorative Arts wearing the “voluminous, chaste garments and heavy jewelry of Central Asian women.”[6] Her manner and dress contrasted vividly with the pseudo-oriental “unclothed ‘eastern’ dancers plying their trade in the Paris Music halls.”[7] Tamara's dance was genuinely feminine, and perhaps even provocative in its very subtlety, but never vulgar. Through her, the West witnessed an ancient art nurtured by generations of women in the protected seclusion of the ich-kari.

With energy and purpose, Tamara Khanum had changed the nature of Uzbek dance. The old classical pieces tended to be solemn, the movements as confined as the lives of the women who danced them.[8] Tamara Khanum, and other dancers who followed her lead, injected a vibrant new spirit into traditional material.[9] Movements now cover more space, and the body is used to a greater degree.

Tamara Khanum’s valor found another challenge during World War II. Through her performances of dance and music she kept up the morale of a threatened nation and raised enough money to buy a tank to send against the Nazis. She was an officer in the Soviet army. “I wore a uniform, and I carried a pistol,” Tamara Khanum said proudly. “But I never shot anyone!” she exclaimed. “I did my shooting with songs and dances.”

I found myself standing on the threshold of her home accompanied by Uzbekistan’s prima ballerina, Bernara Karieva, whose patient diplomacy had secured this audience. Like a gracious queen, Tamara Khanum welcomed us into her home, looking nothing less than glamorous in a pink and gold caftan. She seized me firmly by the shoulders and propelled me about the room while identifying the members of her family whose pictures graced the walls; all were remarkable for their physical beauty and their accomplishments in various branches of the arts. Here, too, hung photographs of Tamara herself: at age 30, 40, and at 50, in Paris, and in London.

She led me into another, larger room. We stood in the midst of Tamara Khanum’s private museum. Costumes of countless nationalities crowded the racks along the wall, while others hung from coat stands or were draped across dress forms, all silent partners to a dancing career which spanned more than half a century, surviving revolution and world war.

Tamara Khanum introduced her costumes as if they were personal friends. The collection included costumes fashioned from the famed textiles which earned the great Silk Road its illustrious name. An iridescent pink and gold brocade khalat shimmered next to an opulent Bukhara coat of wine velvet encrusted with intricately embroidered arabesques wrought from gold by patient hands. Dresses of riotous khan atlas clamored for attention, exploding with dizzying combinations of color and pattern.

In a silent corner stood a dress form covered by an austere black garment. “My paranja, “explained Tamara Khanum, indicating a grim shroud for the living, a mute specter of Uzbekistan's past.

Tamara Khanum steered me toward a glass case filled with antique Turkic jewelry. Among the treasures, gleamed a delicate jeweled crown of the kind which graced the dancers in old miniatures.

With a regal gesture, Tamara Khanum beckoned me to a table prepared according to the dictates of Central Asian hospitality.

“You are my first American guest,”[10] she announced, and then left the room to reappear with steaming dishes prepared with her own hands. Other guests arrive filling the rooms with more laughter and artistic talk. Tamara Khanum’s generosity make her home an oasis for the leading lights of Tashkent's cultural circles. “It is always like this here,” confided Bernara Karieva, glowing with an obvious admiration.

The hours fled unnoticed. I was jolted back to awareness when I was told my flight to Samarkand would soon leave. I begged to stay and continue my dance lessons but Tamara Khanum was emphatic. “You must see Samarkand. You must see old Uzbekistan and understand us.” Her firm insistence melted my resolve. If Tamara Khanum said I should go to Samarkand, I would go to Samarkand. She kissed me and sent me off, my arms filled with gifts and mementos.

That evening, a cool desert wind swept through the streets of Samarkand, echoing the ghostly hoof beats of conquering hordes. So many struggles, so much strife had passed here. But some of the battles have been worth fighting, and Tamara Khanum was one of his Uzbekistan's most valiant heroines.

ENDNOTES

[1] The paranjah is an opaque, enveloping cloak that covers a woman from the top of her head to her ankles and is worn over the chuchvah, a woven horsehair panel that completely hides the face and upper torso.

[2] Mary Grace Swift, The Art of the Dance in the U.S.S.R. (Notre Dame, Indiana; University of Notre Dame Press, 1968). p. 180

[3] Nurkhon Yuldasheva

[4] Tamara Khanum cited by O.I. Shirokaya, Tamara Khonim. (Tashkent, Gafur Gulam Literature and Art Publishing House, 1973), unnumbered pages.

[5] Swift, p. 181.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Swift, on p. 242, citing Nikolai Elizov, “The Uzbek Dance,” Trud, No. 17, (September 1, 1955), p. 31.

[8] R. Karimova, Tantsy ansamblya Bakhor, (Tashkent, 1979), p. 7.

[9] While I was probably the first American guest in this particular home, I was not the first American guest to be hosted by Tamara Khanum. Langston Hughes beat me by several decades.

In 1984, as a member of an official delegation visiting Seattle’s sister-city, Tashkent, I received a rare invitation to the home of People’s Artist of the USSR, Tamara Khanum, the first woman in Uzbekistan to dance in public. The excerpts below come from my article, "Tamara Khanum: Uzbekistan's Heroine of Dance," which originally appeared in a 1985 issue of Arabesque Magazine and is reprinted here with their permission.

All great dancers sacrifice for their art, but very few risk their lives in this endeavor. Tamara Artemyevna Petrosian[1] placed her life in jeopardy merely by dancing, for the arena she chose was a public one in a land where women courted death for daring to appear unveiled. In her dedication to her art, Tamara became a revolutionary heroine.

Born in the Ferghana region in 1906, Tamara Khanum absorbed the culture and traditions of the Uzbek people although her lineage was Armenian. As a child in pre-revolutionary Turkestan, she grew up in a society where women led circumscribed lives, venturing into public only when concealed in the paranjah.[2] “Women were never allowed to speak with strangers, much less sing or dance in front of them.” [3] Women confined their dancing to the ich-kari, the women’s quarters, and danced for each other.

During the 1920s, when the Bolsheviks consolidated their power, social reforms - including the emancipation of women - accompanied their political and economic changes. In 1927, women gathered in Samarkand’s Registan Square to burn their veils. Many earned death for their boldness.

Tamara Khanum opened a new era for Uzbek arts. Her bravery became a political act when she brought ancient dances out into the brilliant light of the 20th century; public appearances were fraught with genuine danger. She became the target of the Basmachi: traditionalist, anti-communist bands of partisans which challenged Soviet authority. “The Basmachi tried many times to kill me,” recalled Tamara Khanum, “but I escaped. The people helped me; they hid me.” Not all were so lucky. She pointed to an old photograph of a delicate young woman.[4] “She was my student,” Tamara Khanum explained, “but she was killed.” Her grief was still fresh.

The times required that an artist also be a fighter.[5] Those early years passed without glamour or ease. “I danced anywhere,” Tamara Khanum reminisced, “on rooftops, in the streets, in the villages. I remember walking with the baby at my breast, another child at my side, holding my hand, and on my back, a bundle filled with my costumes. Like this I walked to the villages and danced, while in the audience sat women still wearing the paranjah.”

She took her art to Paris where, in 1924, she performed at the World Exhibition of Decorative Arts wearing the “voluminous, chaste garments and heavy jewelry of Central Asian women.”[6] Her manner and dress contrasted vividly with the pseudo-oriental “unclothed ‘eastern’ dancers plying their trade in the Paris Music halls.”[7] Tamara's dance was genuinely feminine, and perhaps even provocative in its very subtlety, but never vulgar. Through her, the West witnessed an ancient art nurtured by generations of women in the protected seclusion of the ich-kari.

With energy and purpose, Tamara Khanum had changed the nature of Uzbek dance. The old classical pieces tended to be solemn, the movements as confined as the lives of the women who danced them.[8] Tamara Khanum, and other dancers who followed her lead, injected a vibrant new spirit into traditional material.[9] Movements now cover more space, and the body is used to a greater degree.

Tamara Khanum’s valor found another challenge during World War II. Through her performances of dance and music she kept up the morale of a threatened nation and raised enough money to buy a tank to send against the Nazis. She was an officer in the Soviet army. “I wore a uniform, and I carried a pistol,” Tamara Khanum said proudly. “But I never shot anyone!” she exclaimed. “I did my shooting with songs and dances.”

I found myself standing on the threshold of her home accompanied by Uzbekistan’s prima ballerina, Bernara Karieva, whose patient diplomacy had secured this audience. Like a gracious queen, Tamara Khanum welcomed us into her home, looking nothing less than glamorous in a pink and gold caftan. She seized me firmly by the shoulders and propelled me about the room while identifying the members of her family whose pictures graced the walls; all were remarkable for their physical beauty and their accomplishments in various branches of the arts. Here, too, hung photographs of Tamara herself: at age 30, 40, and at 50, in Paris, and in London.

She led me into another, larger room. We stood in the midst of Tamara Khanum’s private museum. Costumes of countless nationalities crowded the racks along the wall, while others hung from coat stands or were draped across dress forms, all silent partners to a dancing career which spanned more than half a century, surviving revolution and world war.

Tamara Khanum introduced her costumes as if they were personal friends. The collection included costumes fashioned from the famed textiles which earned the great Silk Road its illustrious name. An iridescent pink and gold brocade khalat shimmered next to an opulent Bukhara coat of wine velvet encrusted with intricately embroidered arabesques wrought from gold by patient hands. Dresses of riotous khan atlas clamored for attention, exploding with dizzying combinations of color and pattern.

In a silent corner stood a dress form covered by an austere black garment. “My paranja, “explained Tamara Khanum, indicating a grim shroud for the living, a mute specter of Uzbekistan's past.

Tamara Khanum steered me toward a glass case filled with antique Turkic jewelry. Among the treasures, gleamed a delicate jeweled crown of the kind which graced the dancers in old miniatures.

With a regal gesture, Tamara Khanum beckoned me to a table prepared according to the dictates of Central Asian hospitality.

“You are my first American guest,”[10] she announced, and then left the room to reappear with steaming dishes prepared with her own hands. Other guests arrive filling the rooms with more laughter and artistic talk. Tamara Khanum’s generosity make her home an oasis for the leading lights of Tashkent's cultural circles. “It is always like this here,” confided Bernara Karieva, glowing with an obvious admiration.

The hours fled unnoticed. I was jolted back to awareness when I was told my flight to Samarkand would soon leave. I begged to stay and continue my dance lessons but Tamara Khanum was emphatic. “You must see Samarkand. You must see old Uzbekistan and understand us.” Her firm insistence melted my resolve. If Tamara Khanum said I should go to Samarkand, I would go to Samarkand. She kissed me and sent me off, my arms filled with gifts and mementos.

That evening, a cool desert wind swept through the streets of Samarkand, echoing the ghostly hoof beats of conquering hordes. So many struggles, so much strife had passed here. But some of the battles have been worth fighting, and Tamara Khanum was one of his Uzbekistan's most valiant heroines.

ENDNOTES

[1] The paranjah is an opaque, enveloping cloak that covers a woman from the top of her head to her ankles and is worn over the chuchvah, a woven horsehair panel that completely hides the face and upper torso.

[2] Mary Grace Swift, The Art of the Dance in the U.S.S.R. (Notre Dame, Indiana; University of Notre Dame Press, 1968). p. 180

[3] Nurkhon Yuldasheva

[4] Tamara Khanum cited by O.I. Shirokaya, Tamara Khonim. (Tashkent, Gafur Gulam Literature and Art Publishing House, 1973), unnumbered pages.

[5] Swift, p. 181.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Swift, on p. 242, citing Nikolai Elizov, “The Uzbek Dance,” Trud, No. 17, (September 1, 1955), p. 31.

[8] R. Karimova, Tantsy ansamblya Bakhor, (Tashkent, 1979), p. 7.

[9] While I was probably the first American guest in this particular home, I was not the first American guest to be hosted by Tamara Khanum. Langston Hughes beat me by several decades.

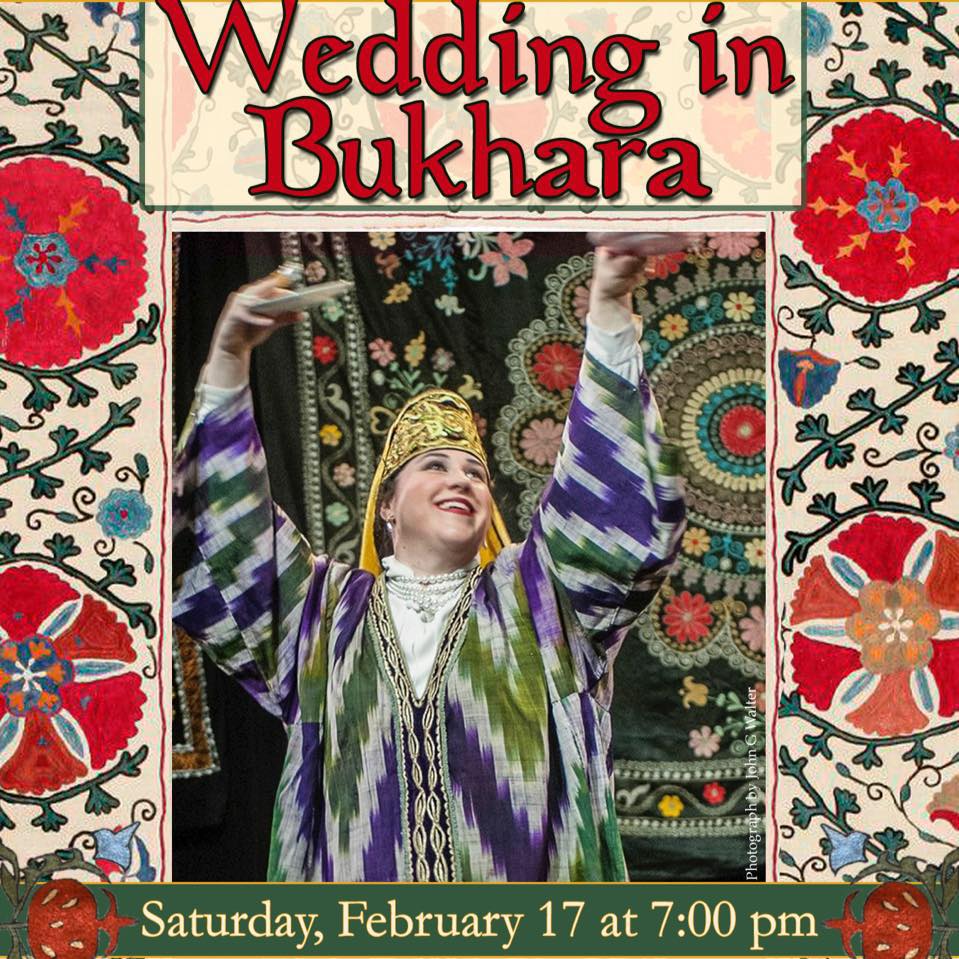

Silk Road Dance Company

Kicks Off Silver Anniversary at

Intersections Festival

February 18, 2020 by Leslie Holleran

What better way to launch a dance company’s 25th year than with a sumptuous performance? And so, Silk Road Dance Company will perform The Golden Road to Samarkand at Atlas Performing Arts Center’s Intersections Festival in Washington, D.C., on February 22.

CLICK HERE FOR COMPLETE ARTICLE

What better way to launch a dance company’s 25th year than with a sumptuous performance? And so, Silk Road Dance Company will perform The Golden Road to Samarkand at Atlas Performing Arts Center’s Intersections Festival in Washington, D.C., on February 22.

CLICK HERE FOR COMPLETE ARTICLE

Discover Uzbek Dance!

Founded in 1985, by Dr. Laurel Victoria Gray the Uzbek Dance and Culture Society builds bridges of understanding between East and West through the preservation and promulgation of traditional Central Asian arts.

Activities include cultural exchange programs, concert tours, lectures, dance demonstrations, master classes with leading Uzbek artists, and other events.

The Uzbek Dance and Culture Society (UDCS) organized the U.S. tours for the "Artists of Uzbekistan" (1989) and the "Uzbekistan Folklore Ensemble" (1990), as well as assisting with the 2001 Kennedy Center concert by Tashkent's Ensemble Munojot.

In 1988, at the invitation of Uzbekistan's Union of Theatrical Workers, the Uzbek Dance and Culture Society traveled to Uzbekistan and Georgia. The historic 1989 delegation, with 30 participants, returned to Uzbekistan to work closely with artists from Tashkent's professional theatres.

Since 1995, the Central Asian Dance Camp has provided opportunities for Americans to study traditional Uzbek, Tajik, Uighur, Afghan and Persian dance with master instructors. The first camps took place in Santa Fe, New Mexico, then relocated to Washington, DC, where they have been held at various locations, including the Embassy of the Republic of Uzbekistan. (See photos below from 2000 and 2019.)

Central Asian Dance Camp venues are usually spacious dance studios with mirrors. Meals prepared by professional chefs are often provided for the partipants. A Silk Road Bazaar offers dance costumes, music, and other hard-to-find items for sale.

The Uzbek Dance and Culture Society has hosted leading Uzbek artists including Qizlarhon Dusmuhamedova, Qadir Muminov, Viktoria "Viloyat" Akilova, Shakir Ahmedov, Habibulla Rasulov, as well as the Uzbekistan Dance Ensemble.

Activities include cultural exchange programs, concert tours, lectures, dance demonstrations, master classes with leading Uzbek artists, and other events.

The Uzbek Dance and Culture Society (UDCS) organized the U.S. tours for the "Artists of Uzbekistan" (1989) and the "Uzbekistan Folklore Ensemble" (1990), as well as assisting with the 2001 Kennedy Center concert by Tashkent's Ensemble Munojot.

In 1988, at the invitation of Uzbekistan's Union of Theatrical Workers, the Uzbek Dance and Culture Society traveled to Uzbekistan and Georgia. The historic 1989 delegation, with 30 participants, returned to Uzbekistan to work closely with artists from Tashkent's professional theatres.

Since 1995, the Central Asian Dance Camp has provided opportunities for Americans to study traditional Uzbek, Tajik, Uighur, Afghan and Persian dance with master instructors. The first camps took place in Santa Fe, New Mexico, then relocated to Washington, DC, where they have been held at various locations, including the Embassy of the Republic of Uzbekistan. (See photos below from 2000 and 2019.)

Central Asian Dance Camp venues are usually spacious dance studios with mirrors. Meals prepared by professional chefs are often provided for the partipants. A Silk Road Bazaar offers dance costumes, music, and other hard-to-find items for sale.

The Uzbek Dance and Culture Society has hosted leading Uzbek artists including Qizlarhon Dusmuhamedova, Qadir Muminov, Viktoria "Viloyat" Akilova, Shakir Ahmedov, Habibulla Rasulov, as well as the Uzbekistan Dance Ensemble.