Remembering Tamara Khanum,

Uzbekistan's Heroine of Dance

"I realized that my love for national music and dance is not a“disease” from which I should be cured, but a worthy sense of love for the creativity of the people who raised and nourished me."

TAMARA KHANUM

TAMARA KHANUM

PREFACE:

In 1984, as a member of an official delegation visiting Seattle’s sister-city, Tashkent, I received a rare invitation to the home of People’s Artist of the USSR, Tamara Khanum, the first woman in Uzbekistan to dance in public. The excerpts below come from my article, "Tamara Khanum: Uzbekistan's Heroine of Dance," which originally appeared in a 1985 issue of Arabesque Magazine and is reprinted here with their permission. This meeting proved to be the first of subsequent visits in 1988 and 1989. The first acquaintance was beginning of a friendship that continued until her passing in 1991. Over the years, she sent me several letters and gifted me with Uzbek treasures, including a costume and an antique Uzbek necklace. Her generosity and advice have guided my dance career.

PHOTO: 1989 visit to the home of Tamara Khanum by some delegation members of the Seattle Tashkent Theater Arts Exchange.

Tamara Khanum, top center, Laurel Victoria Gray (left),

Helen Noreen (right), Kizlarkhon Dusmukhamedova, (lower center.)

In 1984, as a member of an official delegation visiting Seattle’s sister-city, Tashkent, I received a rare invitation to the home of People’s Artist of the USSR, Tamara Khanum, the first woman in Uzbekistan to dance in public. The excerpts below come from my article, "Tamara Khanum: Uzbekistan's Heroine of Dance," which originally appeared in a 1985 issue of Arabesque Magazine and is reprinted here with their permission. This meeting proved to be the first of subsequent visits in 1988 and 1989. The first acquaintance was beginning of a friendship that continued until her passing in 1991. Over the years, she sent me several letters and gifted me with Uzbek treasures, including a costume and an antique Uzbek necklace. Her generosity and advice have guided my dance career.

PHOTO: 1989 visit to the home of Tamara Khanum by some delegation members of the Seattle Tashkent Theater Arts Exchange.

Tamara Khanum, top center, Laurel Victoria Gray (left),

Helen Noreen (right), Kizlarkhon Dusmukhamedova, (lower center.)

TAMARA KHANUM: Uzbekistan's Heroine of Dance

by Laurel Victoria Gray

All great dancers sacrifice for their art, but very few risk their lives in this endeavor. Tamara Artemyevna Petrosian[1] placed her life in jeopardy merely by dancing, for the arena she chose was a public one in a land where women courted death for daring to appear unveiled. In her dedication to her art, Tamara became a revolutionary heroine.

Born in the Ferghana region in 1906, Tamara Khanum absorbed the culture and traditions of the Uzbek people although her lineage was Armenian. As a child in pre-revolutionary Turkestan, she grew up in a society where women led circumscribed lives, venturing into public only when concealed in the paranjah.[2] “Women were never allowed to speak with strangers, much less sing or dance in front of them.” [3] Women confined their dancing to the ich-kari, the women’s quarters, and danced for each other.

During the 1920s, when the Bolsheviks consolidated their power, social reforms - including the emancipation of women - accompanied their political and economic changes. In 1927, women gathered in Samarkand’s Registan Square to burn their veils. Many earned death for their boldness.

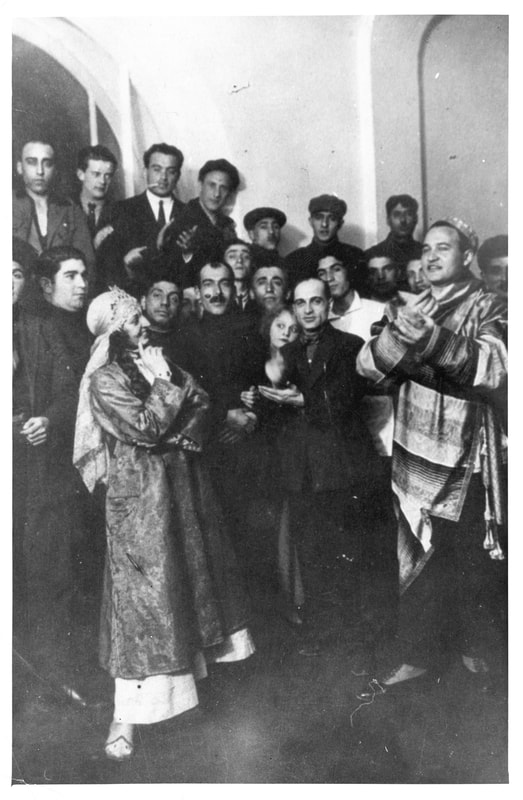

Tamara Khanum opened a new era for Uzbek arts. Her bravery became a political act when she brought ancient dances out into the brilliant light of the 20th century; public appearances were fraught with genuine danger. She became the target of the Basmachi: traditionalist, anti-communist bands of partisans which challenged Soviet authority. “The Basmachi tried many times to kill me,” recalled Tamara Khanum, “but I escaped. The people helped me; they hid me.” Not all were so lucky. She pointed to an old photograph of a delicate young woman.[4] “She was my student,” Tamara Khanum explained, “but she was killed.” Her grief was still fresh.

The times required that an artist also be a fighter.[5] Those early years passed without glamour or ease. “I danced anywhere,” Tamara Khanum reminisced, “on rooftops, in the streets, in the villages. I remember walking with the baby at my breast, another child at my side, holding my hand, and on my back, a bundle filled with my costumes. Like this I walked to the villages and danced, while in the audience sat women still wearing the paranjah.”

She took her art to Paris where, in 1925, she performed at the World Exhibition of Decorative Arts wearing the “voluminous, chaste garments and heavy jewelry of Central Asian women.”[6] Her manner and dress contrasted vividly with the pseudo-oriental “unclothed ‘eastern’ dancers plying their trade in the Paris Music halls.”[7] Tamara's dance was genuinely feminine, and perhaps even provocative in its very subtlety, but never vulgar. Through her, the West witnessed an ancient art nurtured by generations of women in the protected seclusion of the ich-kari.

With energy and purpose, Tamara Khanum had changed the nature of Uzbek dance. The old classical pieces tended to be solemn, the movements as confined as the lives of the women who danced them.[8] Tamara Khanum, and other dancers who followed her lead, injected a vibrant new spirit into traditional material.[9] Movements now cover more space, and the body is used to a greater degree.

Tamara Khanum’s valor found another challenge during World War II. Through her performances of dance and music she kept up the morale of a threatened nation and raised enough money to buy a tank to send against the Nazis. She was an officer in the Soviet army. “I wore a uniform, and I carried a pistol,” Tamara Khanum said proudly. “But I never shot anyone!” she exclaimed. “I did my shooting with songs and dances.”

I found myself standing on the threshold of her home accompanied by Uzbekistan’s prima ballerina, Bernara Karieva, whose patient diplomacy had secured this audience. Like a gracious queen, Tamara Khanum welcomed us into her home, looking nothing less than glamorous in a pink and gold caftan. She seized me firmly by the shoulders and propelled me about the room while identifying the members of her family whose pictures graced the walls; all were remarkable for their physical beauty and their accomplishments in various branches of the arts. Here, too, hung photographs of Tamara herself: at age 30, 40, and at 50, in Paris, and in London.

She led me into another, larger room. We stood in the midst of Tamara Khanum’s private museum. Costumes of countless nationalities crowded the racks along the wall, while others hung from coat stands or were draped across dress forms, all silent partners to a dancing career which spanned more than half a century, surviving revolution and world war.

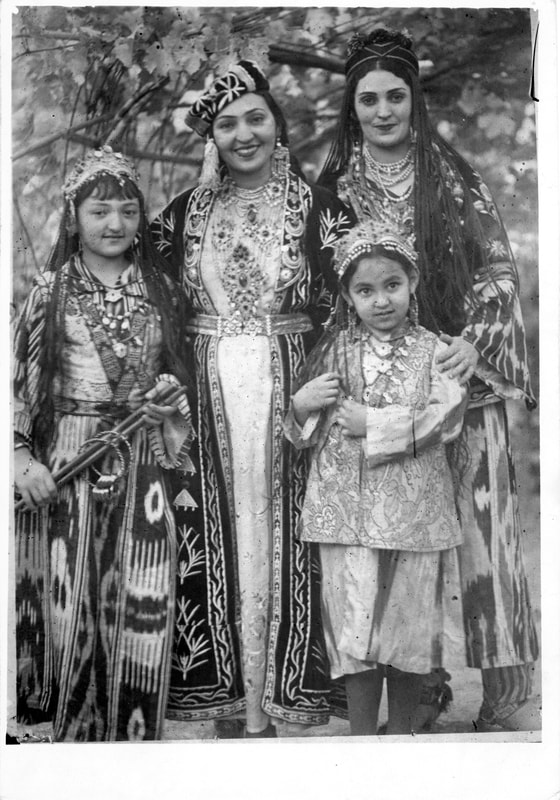

Tamara Khanum introduced her costumes as if they were personal friends. The collection included costumes fashioned from the famed textiles which earned the great Silk Road its illustrious name. An iridescent pink and gold brocade khalat shimmered next to an opulent Bukhara coat of wine velvet encrusted with intricately embroidered arabesques wrought from gold by patient hands. Dresses of riotous khan atlas clamored for attention, exploding with dizzying combinations of color and pattern.

In a silent corner stood a dress form covered by an austere black garment. “My paranja, “explained Tamara Khanum, indicating a grim shroud for the living, a mute specter of Uzbekistan's past.

Tamara Khanum steered me toward a glass case filled with antique Turkic jewelry. Among the treasures, gleamed a delicate jeweled crown of the kind which graced the dancers in old miniatures.

With a regal gesture, Tamara Khanum beckoned me to a table prepared according to the dictates of Central Asian hospitality.

“You are my first American guest,”[10] she announced, and then left the room to reappear with steaming dishes prepared with her own hands. Other guests arrive filling the rooms with more laughter and artistic talk. Tamara Khanum’s generosity make her home an oasis for the leading lights of Tashkent's cultural circles. “It is always like this here,” confided Bernara Karieva, glowing with an obvious admiration.

The hours fled unnoticed. I was jolted back to awareness when I was told my flight to Samarkand would soon leave. I begged to stay and continue my dance lessons but Tamara Khanum was emphatic. “You must see Samarkand. You must see old Uzbekistan and understand us.” Her firm insistence melted my resolve. If Tamara Khanum said I should go to Samarkand, I would go to Samarkand. She kissed me and sent me off, my arms filled with gifts and mementos.

That evening, a cool desert wind swept through the streets of Samarkand, echoing the ghostly hoof beats of conquering hordes. So many struggles, so much strife had passed here. But some of the battles have been worth fighting, and Tamara Khanum was one of his Uzbekistan's most valiant heroines.

[1] Tamara acquired the Uzbek honorific "khanum" when she studied in Moscow at the theatrical institute later known as GITIS, the Russian Insititute of Theatical Art, founded in 1878.

[2] The paranjah is an opaque, enveloping cloak that covers a woman from the top of her head to her ankles and is worn over the chuchvan, a woven horsehair panel that completely hides the face and upper torso.

[3] Mary Grace Swift, The Art of the Dance in the U.S.S.R. (Notre Dame, Indiana; University of Notre Dame Press, 1968). p. 180

[4] Nurkhon Yuldasheva

[5] Tamara Khanum cited by O.I. Shirokaya, Tamara Khonim. (Tashkent, Gafur Gulam Literature and Art Publishing House, 1973).

[6] Swift, p. 181.

[7] Swift, p.181.

[8] Swift, on p. 242, citing Nikolai Elizov, “The Uzbek Dance,” Trud, No. 17, (September 1, 1955), p. 31.

[9] R. Karimova, Tantsy ansamblya Bakhor, (Tashkent, 1979), p. 7.

[10] While I was probably the first American guest in this particular home, I was not the first American guest to be hosted by Tamara Khanum. Langston Hughes beat me by several decades.

by Laurel Victoria Gray

All great dancers sacrifice for their art, but very few risk their lives in this endeavor. Tamara Artemyevna Petrosian[1] placed her life in jeopardy merely by dancing, for the arena she chose was a public one in a land where women courted death for daring to appear unveiled. In her dedication to her art, Tamara became a revolutionary heroine.

Born in the Ferghana region in 1906, Tamara Khanum absorbed the culture and traditions of the Uzbek people although her lineage was Armenian. As a child in pre-revolutionary Turkestan, she grew up in a society where women led circumscribed lives, venturing into public only when concealed in the paranjah.[2] “Women were never allowed to speak with strangers, much less sing or dance in front of them.” [3] Women confined their dancing to the ich-kari, the women’s quarters, and danced for each other.

During the 1920s, when the Bolsheviks consolidated their power, social reforms - including the emancipation of women - accompanied their political and economic changes. In 1927, women gathered in Samarkand’s Registan Square to burn their veils. Many earned death for their boldness.

Tamara Khanum opened a new era for Uzbek arts. Her bravery became a political act when she brought ancient dances out into the brilliant light of the 20th century; public appearances were fraught with genuine danger. She became the target of the Basmachi: traditionalist, anti-communist bands of partisans which challenged Soviet authority. “The Basmachi tried many times to kill me,” recalled Tamara Khanum, “but I escaped. The people helped me; they hid me.” Not all were so lucky. She pointed to an old photograph of a delicate young woman.[4] “She was my student,” Tamara Khanum explained, “but she was killed.” Her grief was still fresh.

The times required that an artist also be a fighter.[5] Those early years passed without glamour or ease. “I danced anywhere,” Tamara Khanum reminisced, “on rooftops, in the streets, in the villages. I remember walking with the baby at my breast, another child at my side, holding my hand, and on my back, a bundle filled with my costumes. Like this I walked to the villages and danced, while in the audience sat women still wearing the paranjah.”

She took her art to Paris where, in 1925, she performed at the World Exhibition of Decorative Arts wearing the “voluminous, chaste garments and heavy jewelry of Central Asian women.”[6] Her manner and dress contrasted vividly with the pseudo-oriental “unclothed ‘eastern’ dancers plying their trade in the Paris Music halls.”[7] Tamara's dance was genuinely feminine, and perhaps even provocative in its very subtlety, but never vulgar. Through her, the West witnessed an ancient art nurtured by generations of women in the protected seclusion of the ich-kari.

With energy and purpose, Tamara Khanum had changed the nature of Uzbek dance. The old classical pieces tended to be solemn, the movements as confined as the lives of the women who danced them.[8] Tamara Khanum, and other dancers who followed her lead, injected a vibrant new spirit into traditional material.[9] Movements now cover more space, and the body is used to a greater degree.

Tamara Khanum’s valor found another challenge during World War II. Through her performances of dance and music she kept up the morale of a threatened nation and raised enough money to buy a tank to send against the Nazis. She was an officer in the Soviet army. “I wore a uniform, and I carried a pistol,” Tamara Khanum said proudly. “But I never shot anyone!” she exclaimed. “I did my shooting with songs and dances.”

I found myself standing on the threshold of her home accompanied by Uzbekistan’s prima ballerina, Bernara Karieva, whose patient diplomacy had secured this audience. Like a gracious queen, Tamara Khanum welcomed us into her home, looking nothing less than glamorous in a pink and gold caftan. She seized me firmly by the shoulders and propelled me about the room while identifying the members of her family whose pictures graced the walls; all were remarkable for their physical beauty and their accomplishments in various branches of the arts. Here, too, hung photographs of Tamara herself: at age 30, 40, and at 50, in Paris, and in London.

She led me into another, larger room. We stood in the midst of Tamara Khanum’s private museum. Costumes of countless nationalities crowded the racks along the wall, while others hung from coat stands or were draped across dress forms, all silent partners to a dancing career which spanned more than half a century, surviving revolution and world war.

Tamara Khanum introduced her costumes as if they were personal friends. The collection included costumes fashioned from the famed textiles which earned the great Silk Road its illustrious name. An iridescent pink and gold brocade khalat shimmered next to an opulent Bukhara coat of wine velvet encrusted with intricately embroidered arabesques wrought from gold by patient hands. Dresses of riotous khan atlas clamored for attention, exploding with dizzying combinations of color and pattern.

In a silent corner stood a dress form covered by an austere black garment. “My paranja, “explained Tamara Khanum, indicating a grim shroud for the living, a mute specter of Uzbekistan's past.

Tamara Khanum steered me toward a glass case filled with antique Turkic jewelry. Among the treasures, gleamed a delicate jeweled crown of the kind which graced the dancers in old miniatures.

With a regal gesture, Tamara Khanum beckoned me to a table prepared according to the dictates of Central Asian hospitality.

“You are my first American guest,”[10] she announced, and then left the room to reappear with steaming dishes prepared with her own hands. Other guests arrive filling the rooms with more laughter and artistic talk. Tamara Khanum’s generosity make her home an oasis for the leading lights of Tashkent's cultural circles. “It is always like this here,” confided Bernara Karieva, glowing with an obvious admiration.

The hours fled unnoticed. I was jolted back to awareness when I was told my flight to Samarkand would soon leave. I begged to stay and continue my dance lessons but Tamara Khanum was emphatic. “You must see Samarkand. You must see old Uzbekistan and understand us.” Her firm insistence melted my resolve. If Tamara Khanum said I should go to Samarkand, I would go to Samarkand. She kissed me and sent me off, my arms filled with gifts and mementos.

That evening, a cool desert wind swept through the streets of Samarkand, echoing the ghostly hoof beats of conquering hordes. So many struggles, so much strife had passed here. But some of the battles have been worth fighting, and Tamara Khanum was one of his Uzbekistan's most valiant heroines.

[1] Tamara acquired the Uzbek honorific "khanum" when she studied in Moscow at the theatrical institute later known as GITIS, the Russian Insititute of Theatical Art, founded in 1878.

[2] The paranjah is an opaque, enveloping cloak that covers a woman from the top of her head to her ankles and is worn over the chuchvan, a woven horsehair panel that completely hides the face and upper torso.

[3] Mary Grace Swift, The Art of the Dance in the U.S.S.R. (Notre Dame, Indiana; University of Notre Dame Press, 1968). p. 180

[4] Nurkhon Yuldasheva

[5] Tamara Khanum cited by O.I. Shirokaya, Tamara Khonim. (Tashkent, Gafur Gulam Literature and Art Publishing House, 1973).

[6] Swift, p. 181.

[7] Swift, p.181.

[8] Swift, on p. 242, citing Nikolai Elizov, “The Uzbek Dance,” Trud, No. 17, (September 1, 1955), p. 31.

[9] R. Karimova, Tantsy ansamblya Bakhor, (Tashkent, 1979), p. 7.

[10] While I was probably the first American guest in this particular home, I was not the first American guest to be hosted by Tamara Khanum. Langston Hughes beat me by several decades.

Gallery

Memorial House Museum of Tamara Khanum

The museum is situated in the center of Tashkent, within walking distance of the Hamid Olimjon Metro Station on the street named after Tamara Khanum. In the home where Tamara Khanum lived the last years of her life, exhibits include items from her extensive collective of folk costumes which she wore in her performances. Photographs, posters, and memorabilia are also on display.

Address: 1/41, Tamara Khanum str., Mirzo Ulugbek district

Telephone: (99871) 267 86 90

Open hours: 10:00AM-05:00PM

Days off: Saturday, Sunday

Address: 1/41, Tamara Khanum str., Mirzo Ulugbek district

Telephone: (99871) 267 86 90

Open hours: 10:00AM-05:00PM

Days off: Saturday, Sunday

Links to more information about Tamara Khanum

|

TAMARA KHANUM at the 1935 London International Folk Dance Festival. "How they met Tamara Khanum in London and the secret of Usto Olim Komilov’s turban"by Rosa Vercoe https://voicesoncentralasia.org/?s=tamara+khanum TAMARA KHANUM performing Uzbek dance in London at 1935 World Dance Festival. https://youtu.be/53_6fh0XmQI TAMARA KHANUM performs Uzbek and Uyghur dance at the 1939 Opening of the Ferghana Canal. https://youtu.be/63fnC9t7rQk TAMARA KHANUM performs Bukharan song and dance. https://youtu.be/7xrJ6d1vxD4 Informal visit by the BLUE GRASS AMBASSADORS to the TAMARA KHANUM museum before the recent remodeling. https://youtu.be/ik6WBQyLf_g TAMARA KHANUM: EDGE OF TOMORROW Film created by students of Webster University in Tashkent. Second half includes scenes of the Tamara Khanum Museum. https://youtu.be/mvKgd2ArgtM Video in Armenian language about TAMARA KHANUM https://www.armtv.com/video/USSR-People-s-Artist-Tamara-Khanum/148997 UZBEK DANCE AND CULTURE SOCIETY

|

Subscribe |